So if you want to sent useful information in a predictable manner, this isn’t the way,” says Kipping.

“Stochastic beacons are more frustrating because you don’t know when the next pulse will come, even if you’ve detected a bunch already. The downside, as with the Wow! signal, is that you also might just confuse your listeners if they can’t manage to catch a repetition. The randomness of the signal could also be thanks to scintillation in the interstellar medium it passes through, especially if it’s traveling more than 100 parsecs (~326 light years) to reach Earth. Sending a signal at random intervals means you avoid the risk of always catching distant listeners during the hours when they’re not actually listening, or hitting a spot on the planet that doesn’t have any radio telescopes operating. That seems like an odd thing to do, but it makes sense if you’re an alien radio astronomer hoping to get noticed by intelligent aliens.

#Seti wow generator

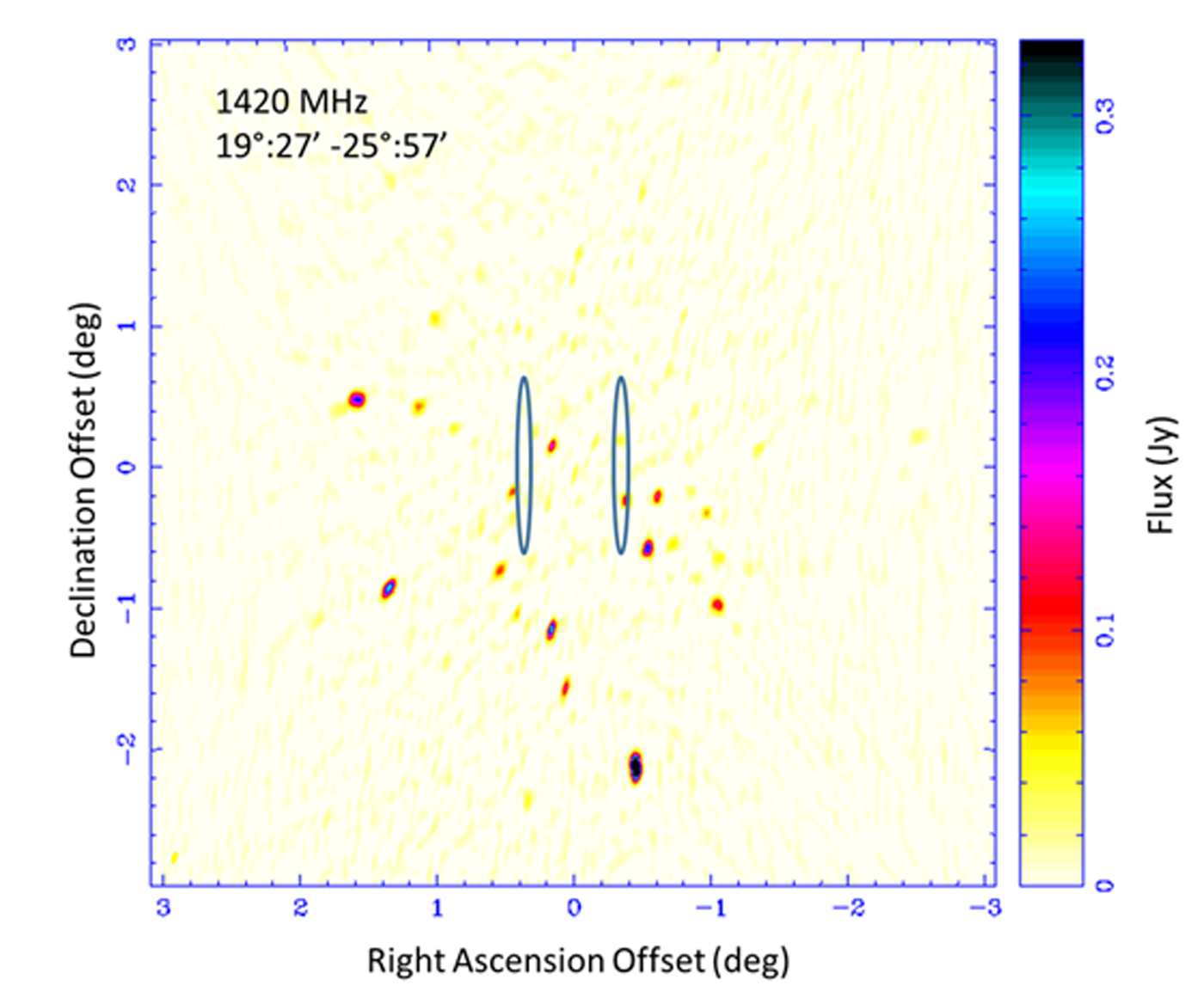

Models can describe how and why the grains stick together, but they can’t predict which grains will bump into each other, or when.Īnd maybe somebody on a planet in the direction of Sagittarius decided to build a radio transmitter that would fire off a signal every X hours, with a random number generator to give the transmitter a new value of X every time. For example, in the early Solar System, the way grains of ice and dust stick together and eventually clump into planets is a stochastic process. Kipping and Gray, in the paper, say there’s another possibility that hasn’t been considered, and it’s called a stochastic repeater.ĭigging Into The Details - Stochastic means, essentially, random - if a process is stochastic, you can model general patterns, but you can’t make specific predictions about when something will happen. Big Ear Radio Observatory and North American AstroPhysical Observator “I’m not saying alien civilizations don’t emit one-off signals - they might well do so - but if they truly only ever sent one signal towards us in both all history and all future time, then the chances of Big Ear seeing it are extremely small, far smaller than the probability of repetition,” he adds.Ī scan of a color copy of the original computer printout. I think we can fully discard that as being absurdly contrived,” Kipping says.

#Seti wow Patch

“The probability of the Wow! patch of sky harboring just one civilization that sent out just one signal, over all of cosmic time, *and* that the Big Ear just happened to be listening to at the right time and at the right spot is extremely small.

Statistically speaking, Ehman and his colleagues should have missed it, too.Īnd if the signal was really a one-time event, the interstellar equivalent of somebody accidentally setting off a car alarm and shutting it down after the first bleep? But with such a long pause between signals, it’s astounding that Big Ear was lucky enough to catch one in progress in the first place. If the signal repeats came any closer together than that, then statistically, somebody should have heard it again. What’s New - The real mystery is this: If the Wow! signal was a beacon from a distant world or something else, why hasn’t anyone heard it since? So far, it’s eluded nearly 200 hours of radio astronomers’ observations, often with more advanced, more sensitive telescopes than the now-retired Big Ear.Īnd to pull that off, according to a 2020 study, there would have to be at least 40 hours of silence between repetitions of the signal (if, of course, the signal actually repeats). In a recent paper, Columbia University astronomer David Kipping and the late astronomer Robert Gray explore an often-overlooked possibility - but as Kipping tells Inverse, there really are no good explanations. And for the last 45 years, scientists have been searching for an explanation.

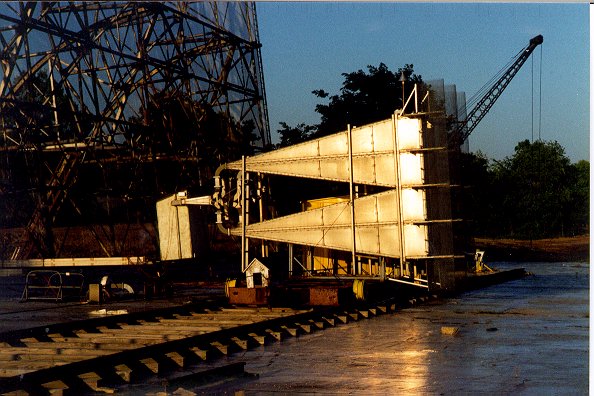

No one ever heard the signal again, despite hundreds of hours of trying. Three minutes later, when Big Ear’s second antenna swept toward Sagittarius, it found only silence. Lead astronomer Jerry Ehman hastily wrote “Wow!” next to the signal on a printout of Big Ear’s data, and it’s been known as the Wow! signal ever since. The Big Ear radio telescope’s first antenna listened to the signal for 72 seconds before moving on in its scheduled sweep of the sky. It had all the features SETI ( Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence) researchers expected to see in an actual alien radio signal. Forty-five years ago, radio astronomers at Ohio State University detected a strong, clear radio signal from somewhere in the direction of the Sagittarius constellation.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)